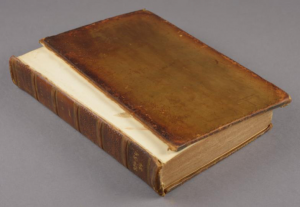

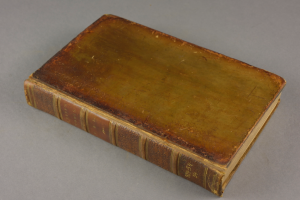

As books are handled and opened over time, one of the most common types of damage that occurs is that the joints break and the boards become detached. During our project conserving the John Stuart Mill collection, we therefore had the task of reattaching the boards of many books – such as this one, volume 10 of Jonathan Swift’s Collected Works:

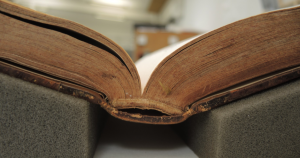

There are multiple ways that conservators can reattach the boards of books, and each time we choose the option that best suits the needs of the particular object. A particularly strong and durable board reattachment technique is called ‘board slotting’, which was developed by Christopher Clarkson during his time working in the conservation department of the Bodleian Libraries. It involves using a specialised machine to cut a slot along the spine-edge of the boards, and then inserting textile flanges into the slots in order to reattach the boards to the text block. It is particularly suitable for books with ‘tube hollows’ – that is, where the leather is not directly adhered to the book’s spine, but instead to a tube of paper that has been glued to the spine beforehand.

Board slotting was judged to be the best option for a number of the books in the collection. First, the hollow of the book is split to allow access to the spine. The spine is then prepared by cleaning away the old linings and glue, and replacing them with layers of strong, flexible, archival materials: namely, Japanese paper and aerocotton. A spine-piece of toned aerocotton is then prepared and glued to the first lining to form extended ‘flanges’ of textile on either side of the spine. This recreates the hollow of the original structure while also forming the basis for the board reattachment.

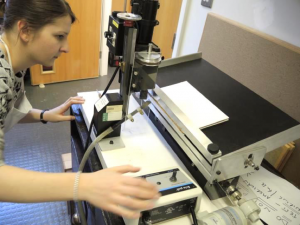

The board slotting is done using a machine adapted by American conservator Jeff Peachey. The textile flanges are then cut to size and inserted into the slots with some adhesive, reuniting the boards in their proper place.

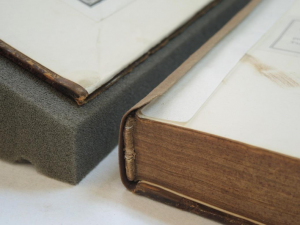

The original spine can then be adhered back in place, giving a neat finish to the conservation treatment.

— Jess Hyslop, Conservator, Oxford Conservation Consortium