Another week of research at Oxford has yielded photos of, in round numbers, 3300 more examples of marginalia on 1500 more pages in 31 more individual volumes. Work this time around was greatly abetted by the ongoing work of Hazel Tubman, Somerville’s Delmas Foundation-funded research assistant.

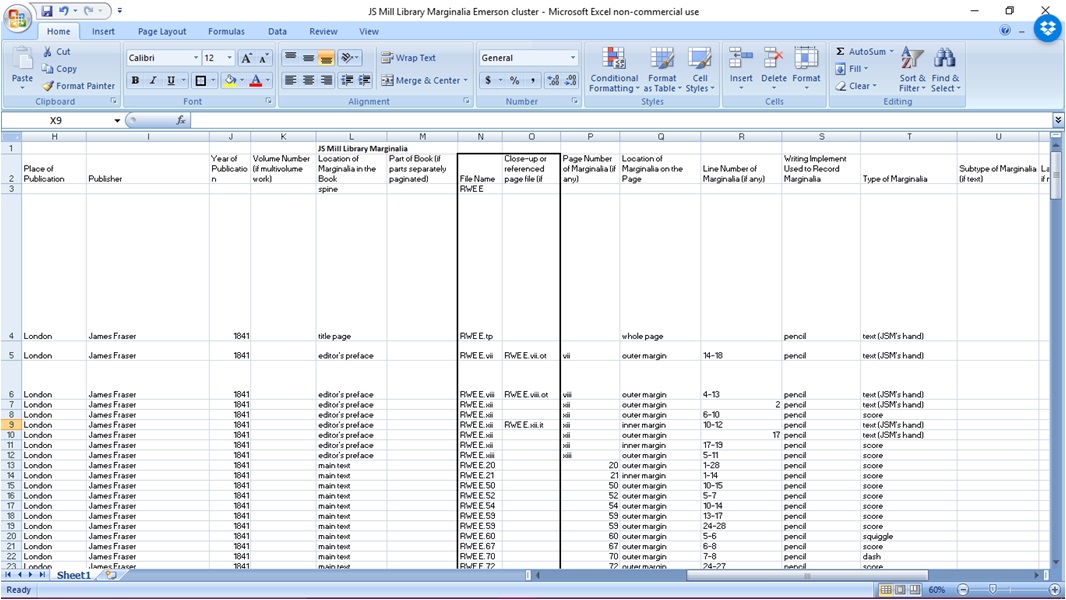

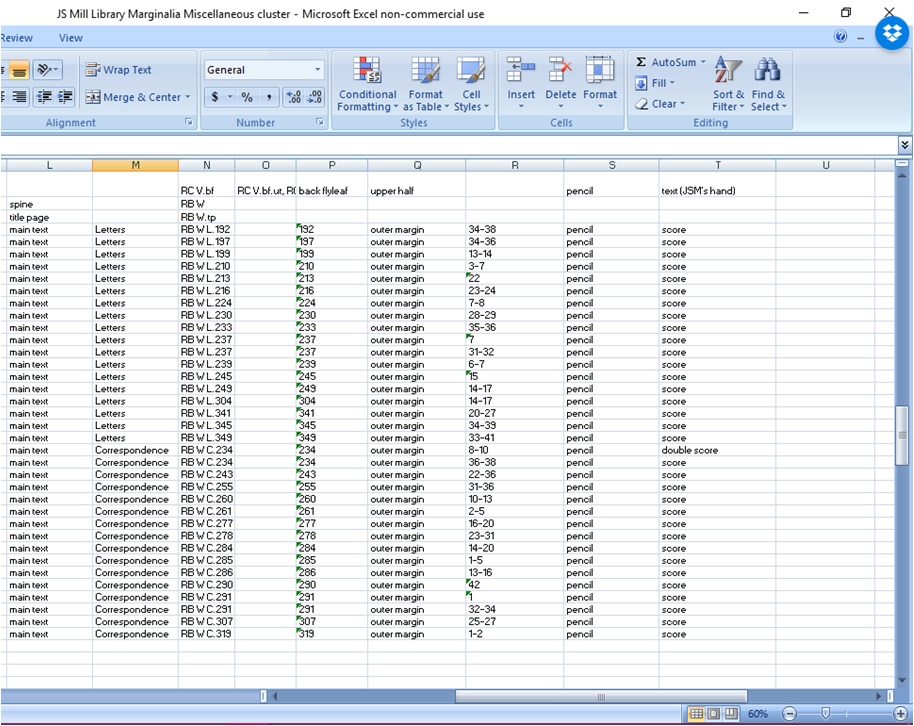

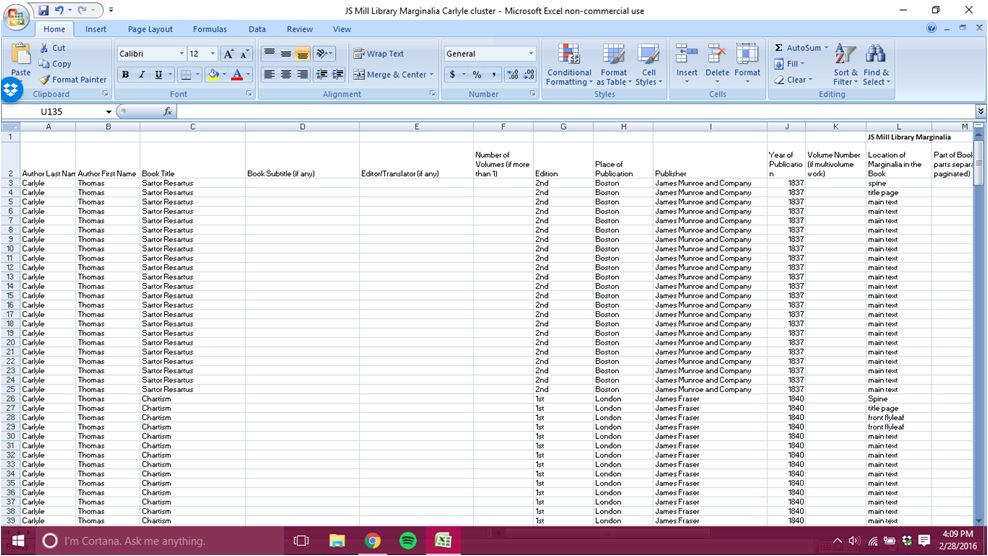

Hazel has begun the first serious effort to identify, collate, and enter into metadata spreadsheets suitable for use with the under-development Mill Marginalia database every single example of marginalia in the John Stuart Mill Collection. We’re all hopeful that Hazel will see her way to writing about her experience in one or more future postings on this site.

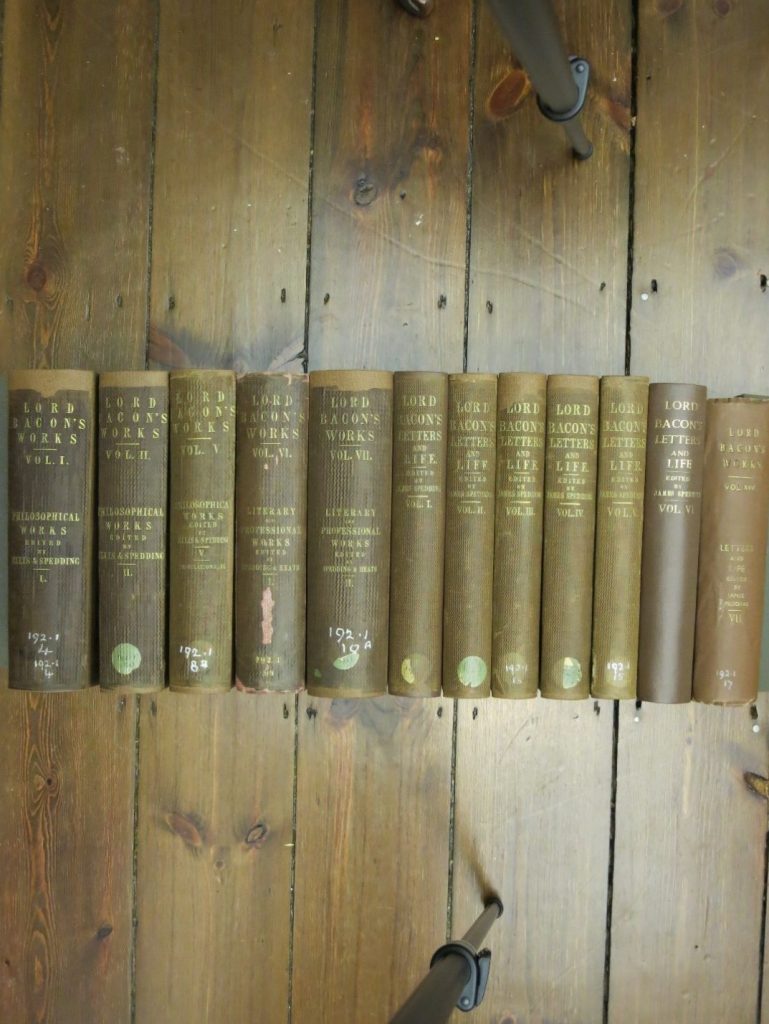

In the meantime, the marginalia from Mill’s copy of the 14-volume Works of Francis Bacon, to cite a singular example, looks promising on at least three fronts.

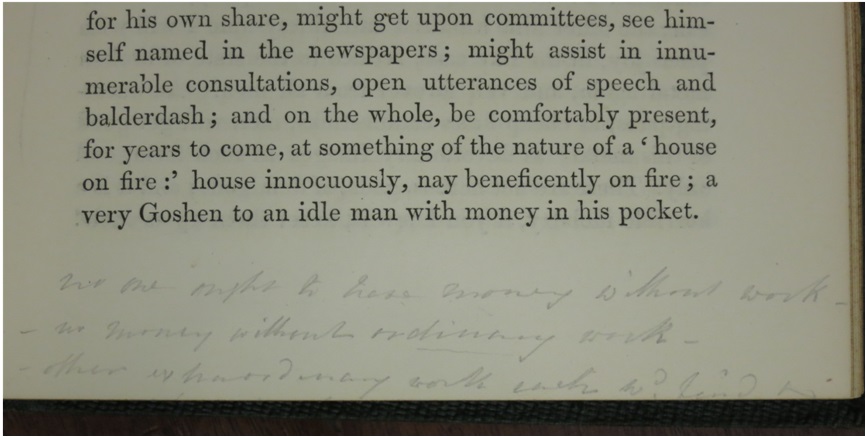

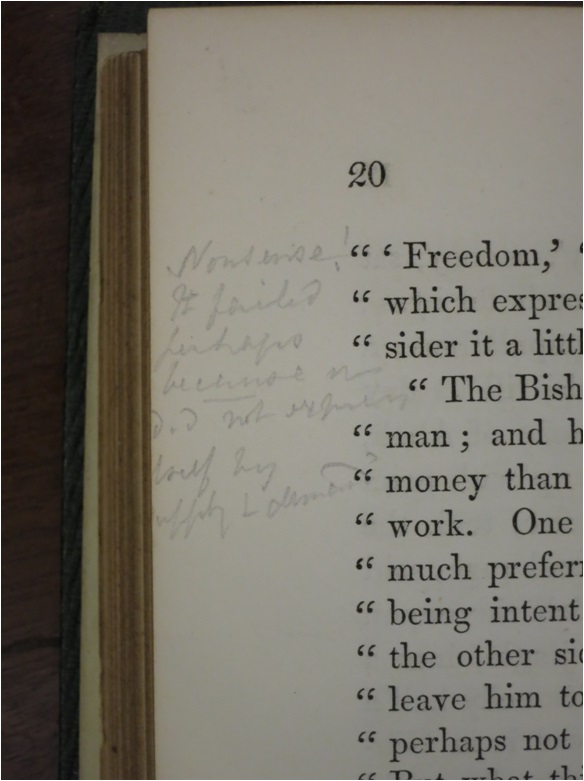

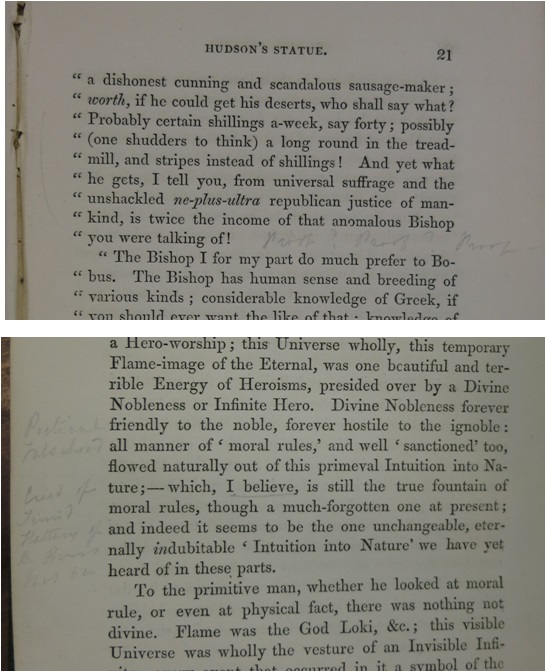

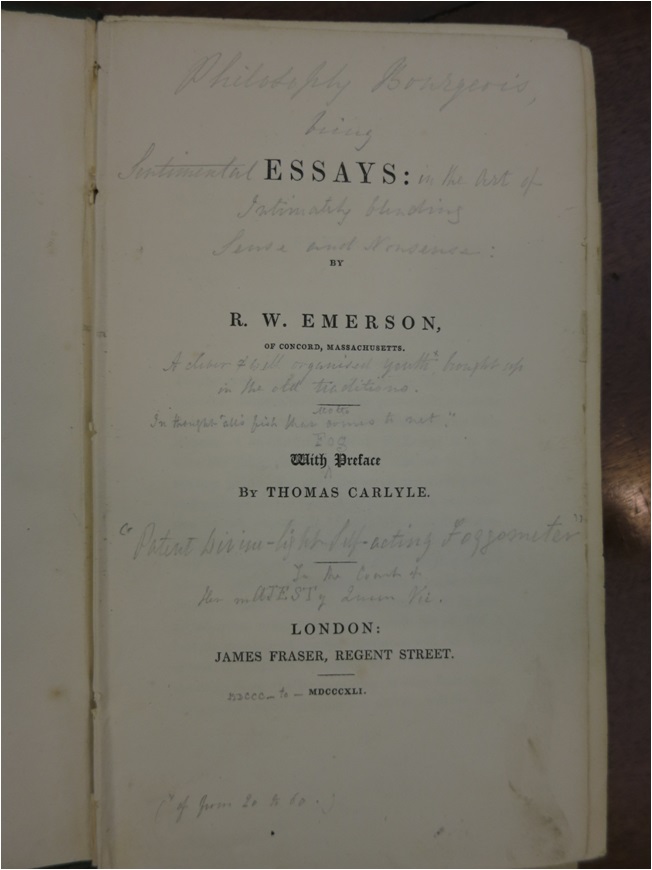

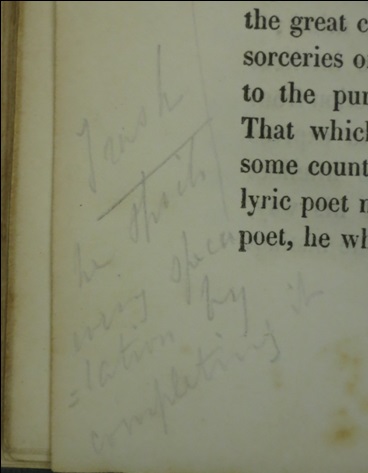

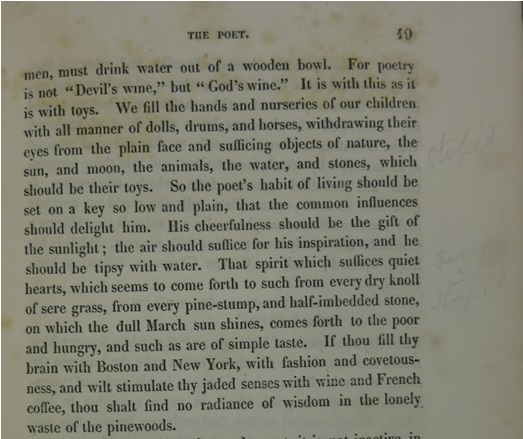

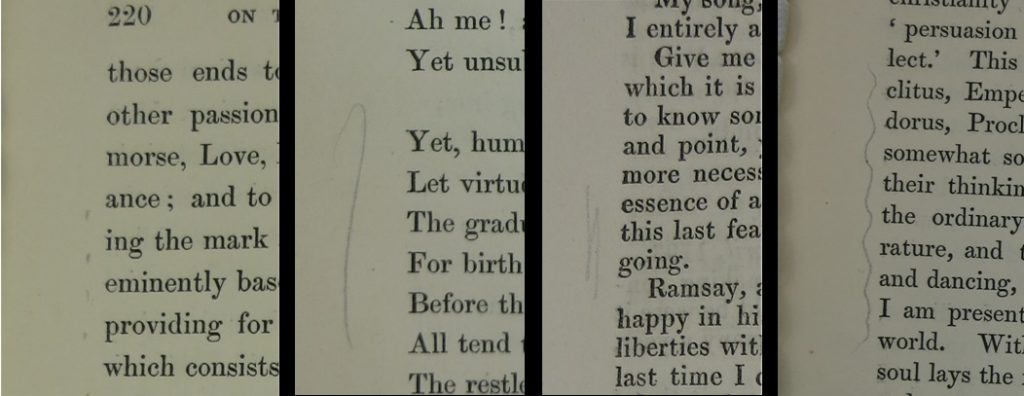

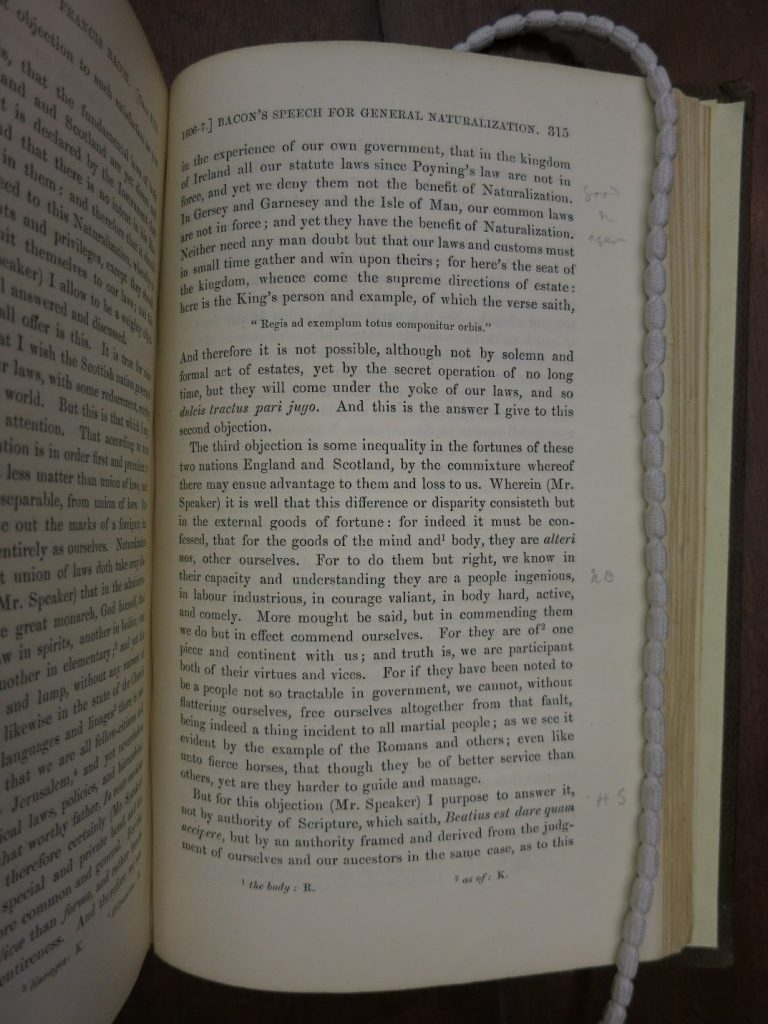

First, it reveals Mill annotating in a new way. Rather than reading as a friend anxious to safeguard the reputation of someone whom he knew personally, as he does in Thomas Carlyle’s Life of John Sterling (about which more in a future post); or reading as a critic quick to point out, if only to himself, the argumentative shortcomings of another writer, as he does in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Essays (for which see Frank Prochaska’s 2014 article in History Today); Mill evidently turned to Bacon’s Works as a researcher eager to find passages suitable for his own future reference. The result was hundreds of marginal scores, double scores, “NB”s, and “HS”s (presumably shorthand for “Holy Scripture,” since it appears beside biblical references). Mill occupies the margins of Bacon’s Works both literally and figurative, noting his predecessor’s experience and opinions without evaluating them as he does in other, more recent authors’ works.

Second, these brief but numerous marks and annotations begin to appear with startling frequency in the tenth volume, which contains a portion of Bacon’s Life and Letters focused in particular on the inner workings of England’s government. This volume was published in 1868, also the final year of Mill’s service in Parliament, and the coincidence of subject matter and date suggests that Mill may have been seeking passages to use in his own late parliamentary speeches. A search for marked and annotated passages from Bacon in the facsimile online edition of Mill’s Collected Works may yield some surprising and previously unknown connections in the future.

Third, Mill’s marginalia in Bacon’s Works suggests the need for, at the least, revision to and expansion of the listing for Bacon in the Bibliographic Index of Persons and Works Cited of Mill’s Collected Works. In Volume XI: Essays on Philosophy and the Classics, for instance, the editors acknowledge the presence of Bacon’s Works in Somerville’s John Stuart Mill Collection, but go on to assert that Mill’s references to Bacon all antedate the edition. However, for all publications after 1857, the year that the first volume of the Bacon appeared, Mill may in fact be quoting from his own edition and may be doing so with much greater breadth and frequency than is presently identified in the Index.

It almost goes without saying, although it should be said, that Somerville was, once again, an incredibly welcoming and comfortable place in which to do research. If only all archives were as pleasant and productive to visit.

– Albert D. Pionke, Project Director