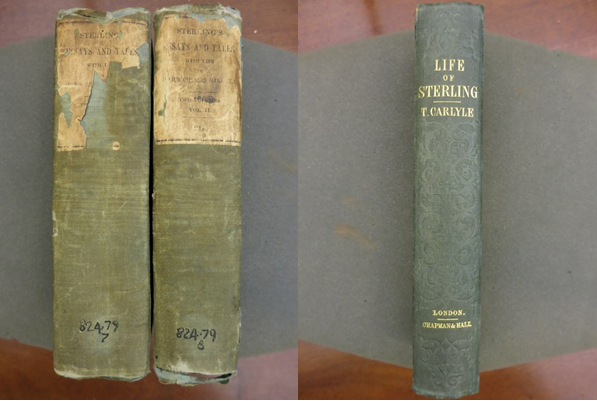

Sandwiched between presentations on Thomas Carlyle’s connections to Robert Owen and Orestes Brownson, respectively, Albert’s “Influence as Palimpsest: Carlyle, Mill, Sterling” met with a warm reception at “The Oak and Acorns: Recovering the Hidden Carlyle,” hosted at The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities. Speaking just steps outside the north gate of Somerville College, Albert placed the marginalia in Mill’s personal copies of John Sterling’s Essays and Tales (1848) and Carlyle’s Life of John Sterling (1851) in the context of Mill’s complex relationship with both men and reviewers’ reactions to both of their books, grounding his presentation in first-ever photos from the Mill Collection.

Mill and Sterling first encountered one another in 1828 at the London Debating Society, whereas Mill first met Carlyle during the latter’s second visit to London in 1831. Mill subsequently introduced his two friends to one another in his London office in 1835, and then elicited contributions from both men to appear alongside his own in the London and Westminster Review. This period of mutual intimacy and influence lasted through the second half of the 1830s, resulting in, among other things, “Carlyle’s Works,” commissioned from Sterling by Mill for the October 1839 issue of the LWR.

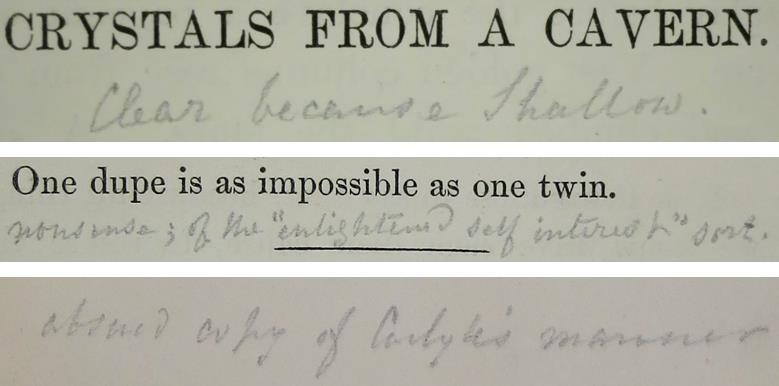

Although this essay was generally recognized as Sterling’s best work by reviewers of the posthumous Essays and Tales, most found the rest of the book largely underwhelming. In this they were not alone, as Mill’s private annotations include judgments like “nonsense; of the ‘enlightened self interest’ sort,” “Clear because Shallow,” and, most relevant for a conference on Carlyle, “absurd copy of Carlyle’s manner.”

Mill also resisted the pious apologetics in the biographical memoir added to Essays and Tales by Charles Julius Hare, archdeacon in the Church of England and one of Sterling’s two literary executors.

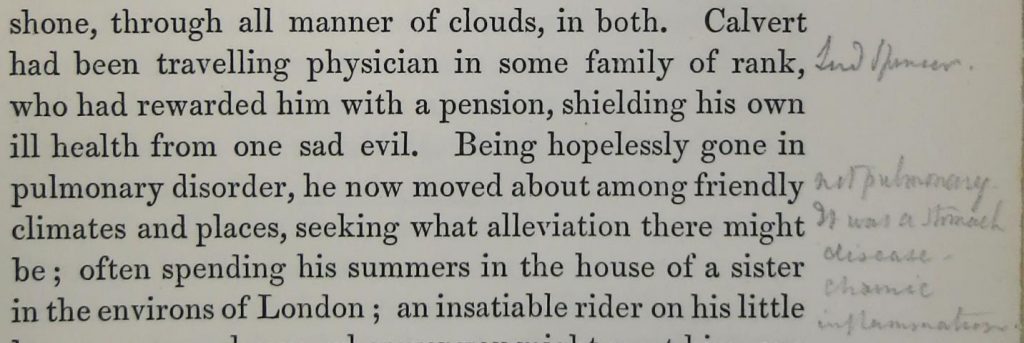

The other of these two executors, Thomas Carlyle, was so dissatisfied with Hare’s efforts, that he published his Life of John Sterling three years later. Reviewers overwhelmingly recognized the superiority of Carlyle’s efforts, and even Mill could find little fault, confining himself mainly to supplying missing and correcting erroneous biographical details in the margins.

Judging from the absence of summative judgments in the front or back pages, Mill appears to have read through the Life once and set it aside without further thought. The relative paucity of his engagement might, itself, be a sign of the state of his deteriorated friendship with Carlyle, as much as evidence for the satisfactions of his newly married life. Either way, Mill’s marginal relations with his ex-friends, the one deceased and the other dyspeptic, helped to provoke an especially robust Q&A session and subsequent conversation, all eminently sensible and enlightened, even when partaking of self-interest.

– Albert D. Pionke, Project Director