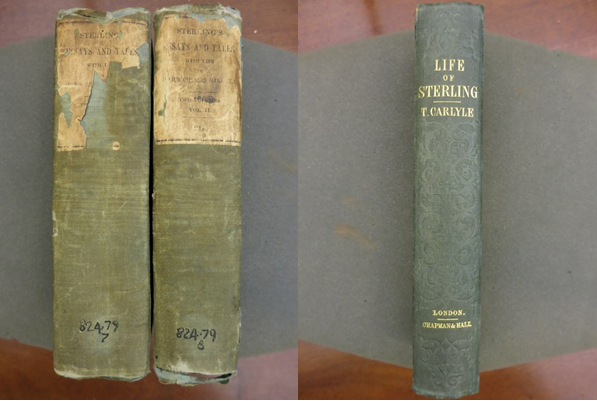

My work on the project began in August 2016 and spanned a few months and various tasks until the end of the semester in December. As I was a research assistant to Dr. Pionke, my job description was basically identical to Carissa’s, so I won’t repeat what she has already written about the job except to say that I spent a great deal of time typing in spreadsheets and attempting to decipher Mill’s handwriting.

Fast-forward a few months, and I have graduated from the University of Alabama, am no longer working on the project, and have managed to stumble into a temporary job in the property department of an insurance company. At first glance, these jobs seem incredibly different. After all, what could the study of margin notes in the books of a nineteenth century writer and philosopher have in common with property insurance? Oddly, more than one would expect.

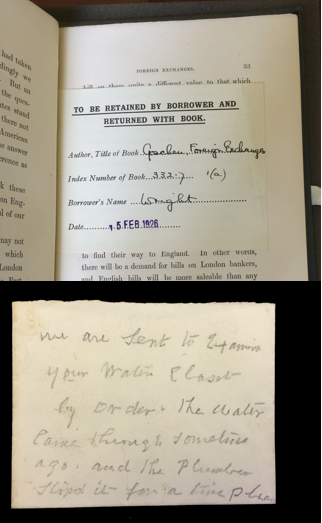

Admittedly, these similarities are mainly logistical in nature. For example, I still spend a great deal of time typing in spreadsheets. Now, instead of information about authors, editors, and publications, it’s policyholders, mortgagees, and personal articles floaters. Excel, however, is a staple program in many operations, and so its role in both academic and insurance spheres is rather unremarkable. The aspect of my insurance job that really caught my attention and drew these parallels in my mind is the amount of time I spend in my cubicle, squinting at haphazardly-scrawled New Business applications for homeowner’s insurance and attempting to decipher policy numbers, addresses, or endorsement descriptions. This task reminded me greatly of pressing my face up close to my computer screen in an attempt to decipher certain margin notes in Mill’s books that verged on indecipherable.

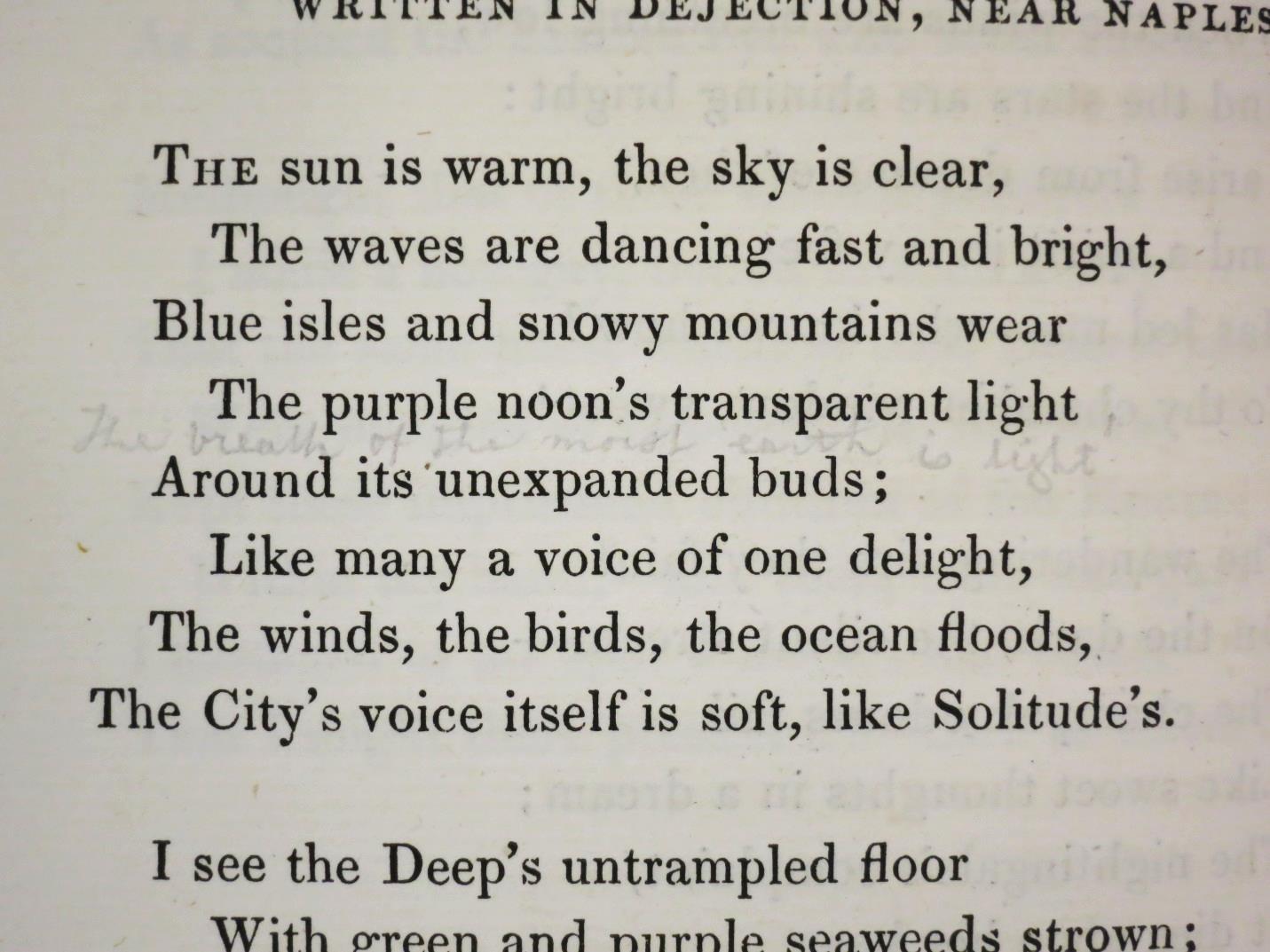

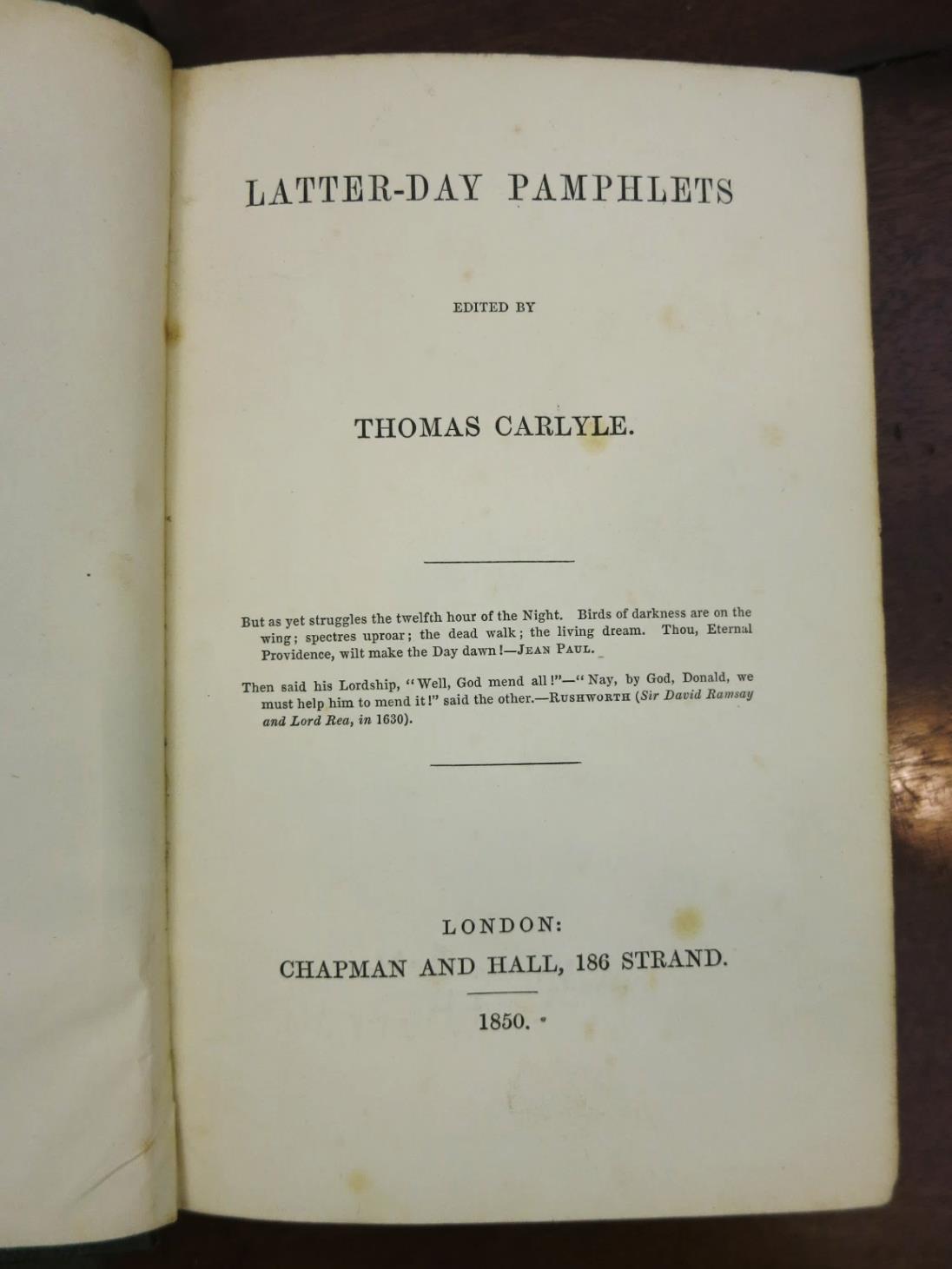

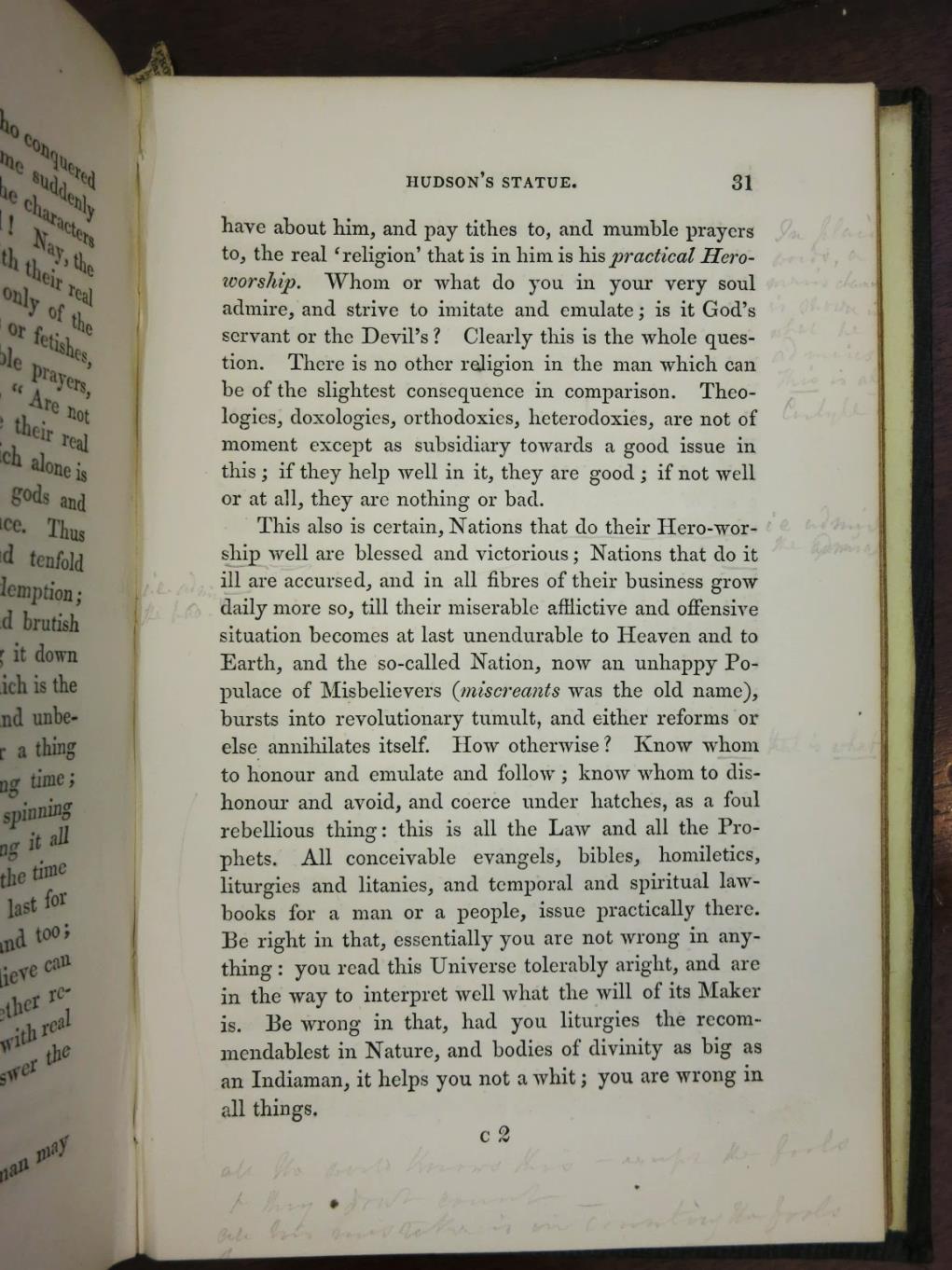

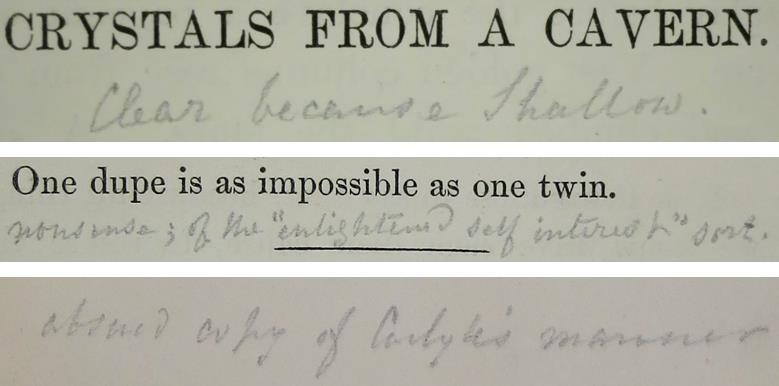

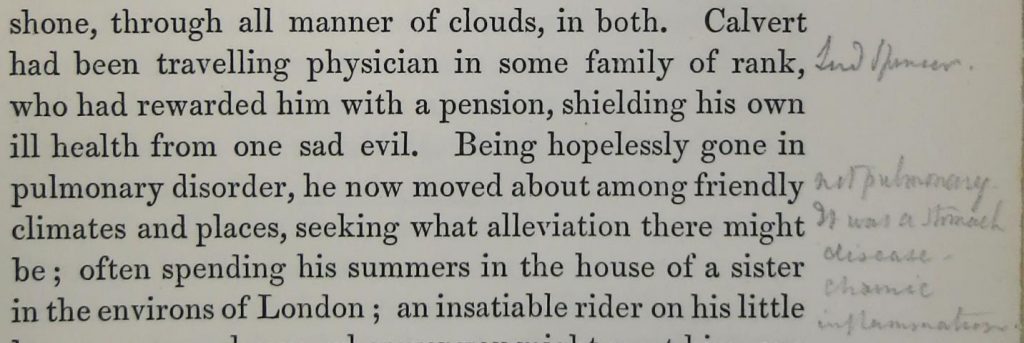

Clearly, insurance and John Stuart Mill differ more than they coincide, but what I find interesting about the overlap in method – however small – is how different avenues for written text yield distinct personae of the writer. For instance, Mill’s longer notes or the notes on full pages at the ends of chapters tend to be much neater than the notes he took while in the midst of reading. These hastily-scribbled notes seem to indicate that in many cases, Mill did not write his margin notes with the intention that they should be read by anyone other than himself. I tried to remind myself of this possibility as I sat hunched over specific margin notes and struggled to decipher letters from the squiggles. Of course, that was not always the case, but the untidy nature of the notes suggests a sort of candidness. Not only was Mill likely too preoccupied with his reading to worry about the neatness of his handwriting, but he also was not going to great lengths to present the critical persona he assumes in his published works.

The similarly-rushed handwriting of insurance applications seems to indicate something different. The obvious answer is that the purpose of these applications is to provide basic, accessible information that is required in order to extend insurance coverage. Yet, the underwriters and not the applicants themselves fill out the applications, and there are occasional instances where the underwriter makes a minor mistake in the address field, for instance. As the amount of insurance coverage and the premium are determined in part by the location of the property, this mistake is one that applicants would be unlikely to make themselves. What this avenue of written text seems to indicate then is an impersonal distance between the writer of the text and the party that is directly affected by it.

To conclude, this was my first experience participating in a research project, and though there were many aspects of the job that interested me, this multi-faceted nature of the written word and its ability to create different personae of the writer has been my main takeaway. I’ve found myself trying to apply these same ideas to the various forms of text I encounter from day to day – from marginalia to insurance applications to text messages to the narrators of the novels post-graduate life has finally allowed me to get around to reading.

— Lauren Davis, Research Assistant To Professor Albert Pionke at the University of Alabama