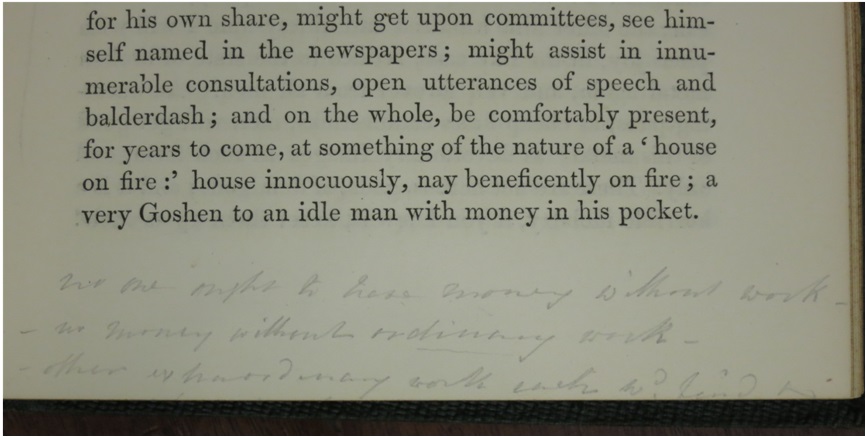

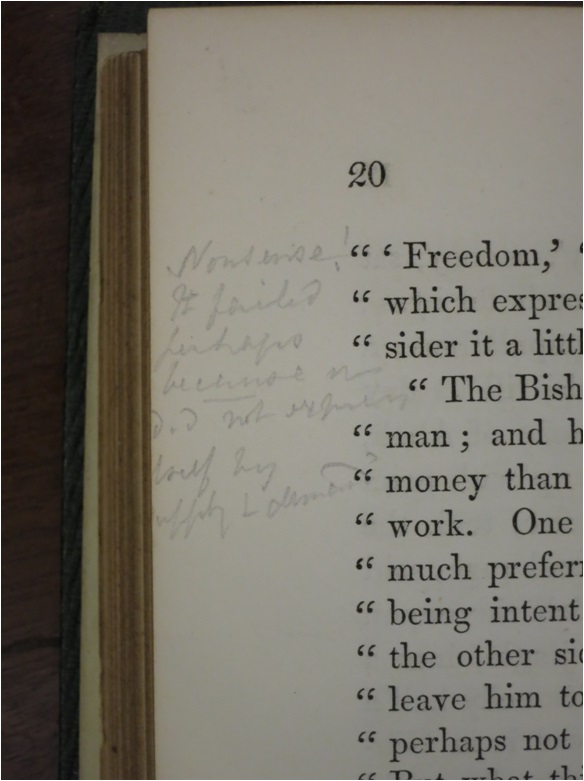

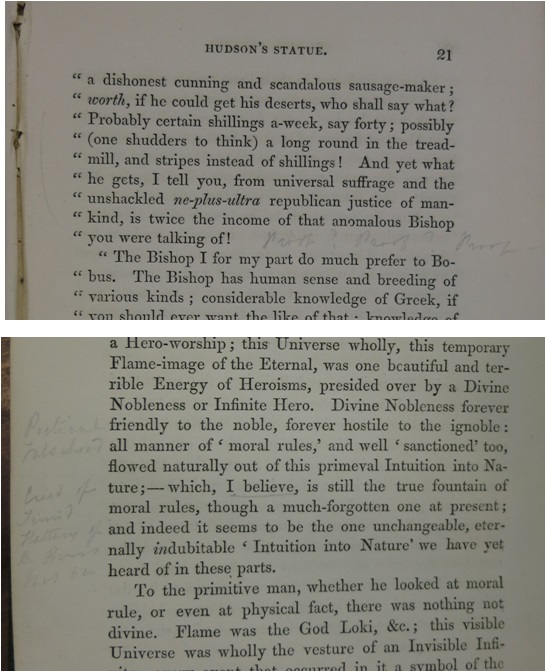

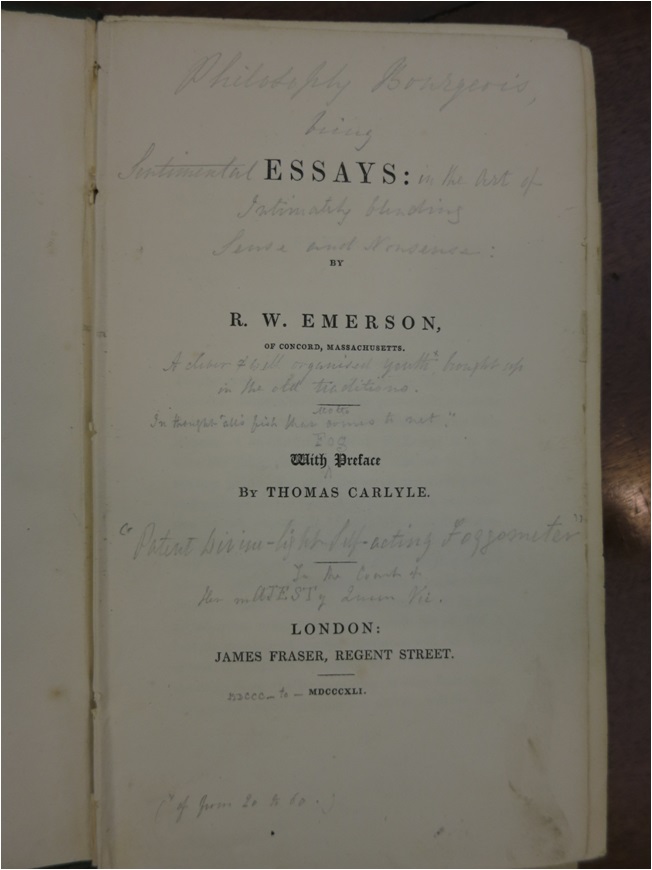

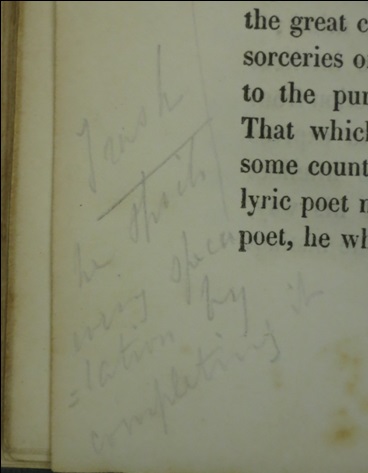

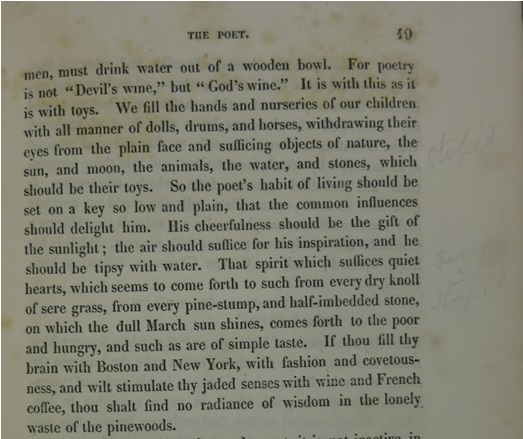

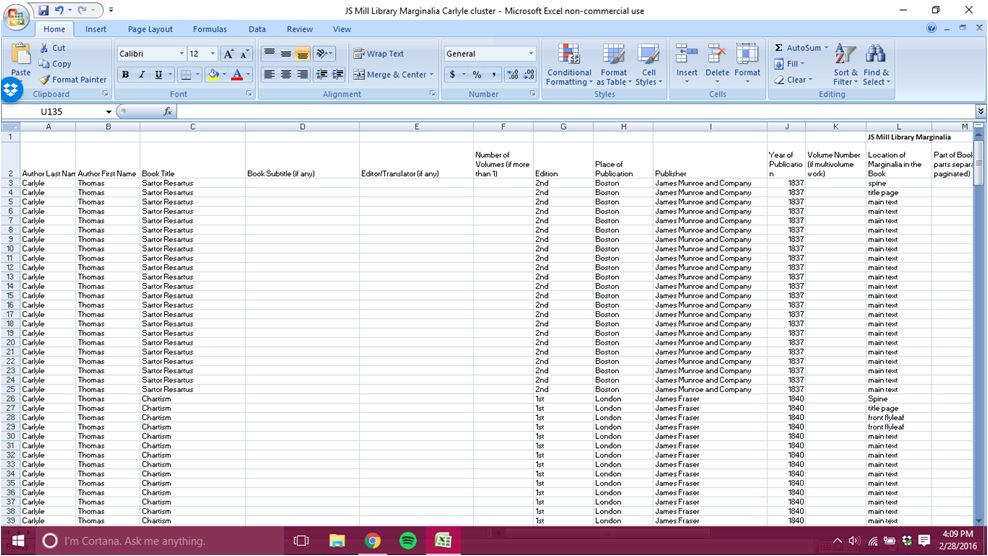

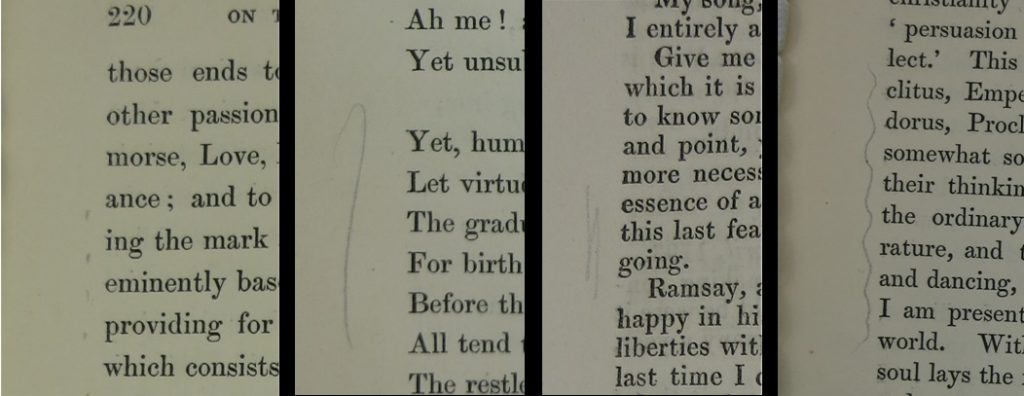

After I filled the spreadsheets, I went back through the 1,906 photos. To ensure quality, Dr. Pionke had taken two photos of each marked page, and occasionally a zoomed-in picture of text blocks. This was helpful while working through the marginalia, but users of the final project wouldn’t really need the duplicates. So my next task was going through the photo sets and paring them down as well as filing them for the database.

I compared each set of duplicates and chose the better photo, rotated it to the appropriate alignment, and renamed the file based on our agreed-upon naming convention (Author Title Volume.Page.OtherInfo). The zoomed-in files we kept, in case users had trouble reading text in the full-page photos.

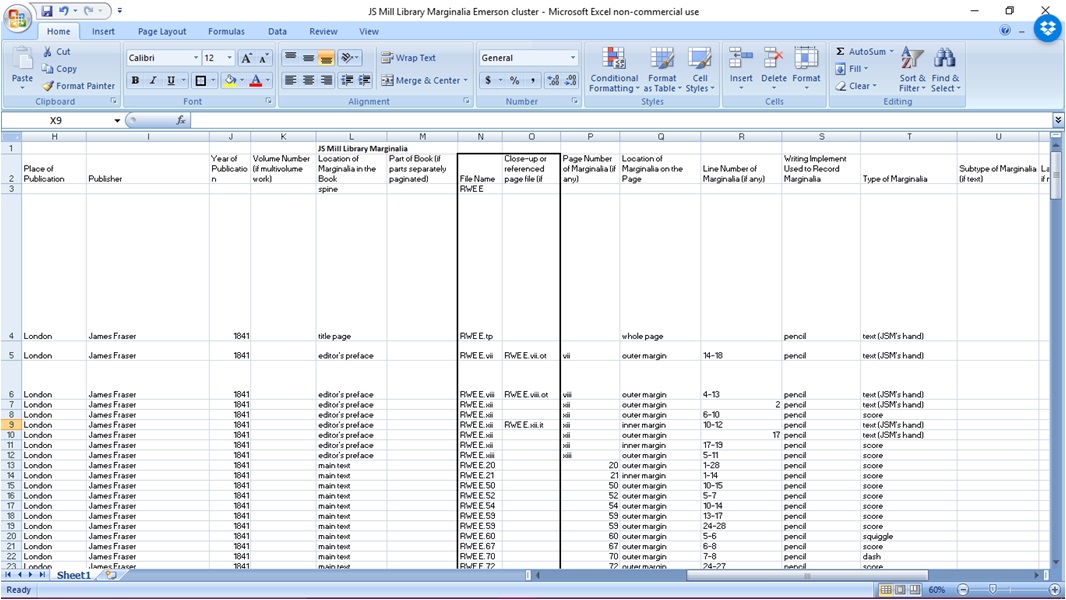

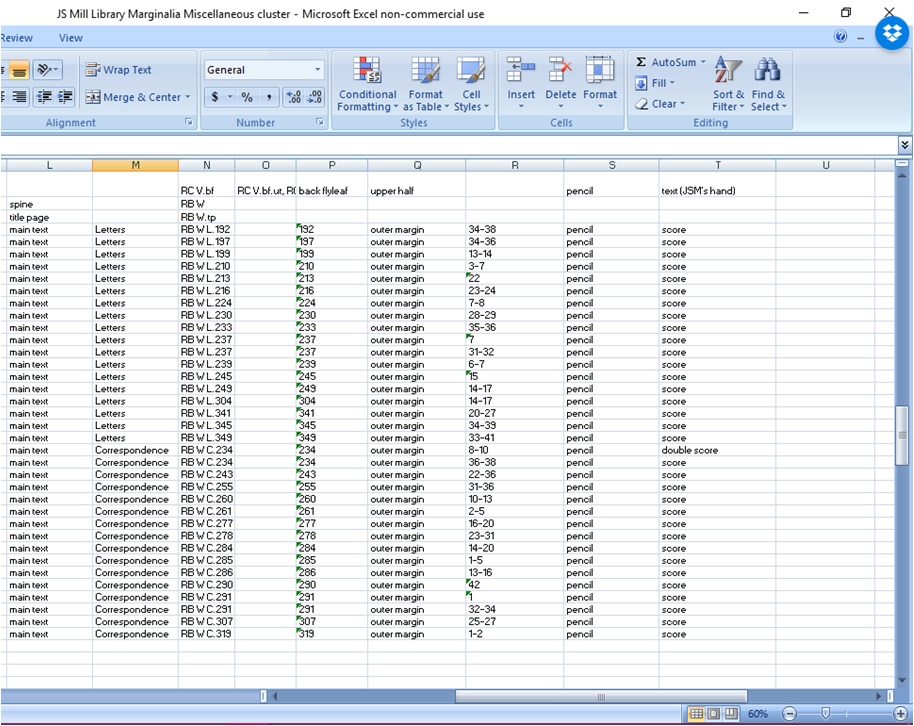

I then added two columns to the spreadsheet to include these file names—one for full-page photos and another for zoomed-in pages. That second column also came in handy for notes in which Mill referenced other pages; the referenced pages went into the same column as the zoomed-in photos.

The inclusion of file names directly in the spreadsheet will make it easier for Tyler (our web design expert) to tie the photos to the information in the final website. I also added rows for unmarked title pages, which we had decided to include in the database.

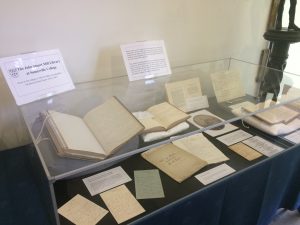

Moving forward, I won’t be doing much with the project. The next step for this section of the project involves choosing the best example of each type of marginalia for a potential reference section of the site, which has already begun.

The process was definitely satisfying in a lot of ways. I started with 1,906 photos and ended with 7 comprehensive sheets of marginalia. I can’t wait to see the future of the project, and I’m very excited about this information being available to the public on a large scale. I’m very glad I got the opportunity to work with this team and learn more about the inner workings of J.S. Mill!

– Carissa Schreiber, former Research Assistant to Professor Albert Pionke at the University of Alabama.