Now nearing the end of my sixth data-gathering trip to Oxford, I have just completed photographing one third of the John Stuart Mill Library. Which is to say that I have finished section D (of L), in which are shelved the numerous editions – American, English, French, German, Greek, and Italian – of Mill’s published works. Also in D are select runs of the London Review, the Westminster Review, and the Examiner, as well as four bound volumes of article offprints, three arranged by year of publication and one devoted exclusively to pieces from the London and Westminster Review during the period (1836-1840) in which Mill was a prolific contributor as well as the de facto editor.

As one might imagine, many of these books and articles testify to Mill’s meticulousness as an editor of his own works. The first edition of his System of Logic (1843), for instance, features a number of the editorial corrections and sentence-level revisions that appear in later editions, and that were subsequently documented by John Robson and his team at Toronto. This is also the case for the first edition of Mill’s Principles of Political Economy (1848), and for many of the essays that he would go to feature in Dissertations and Discussions (1859 and later).

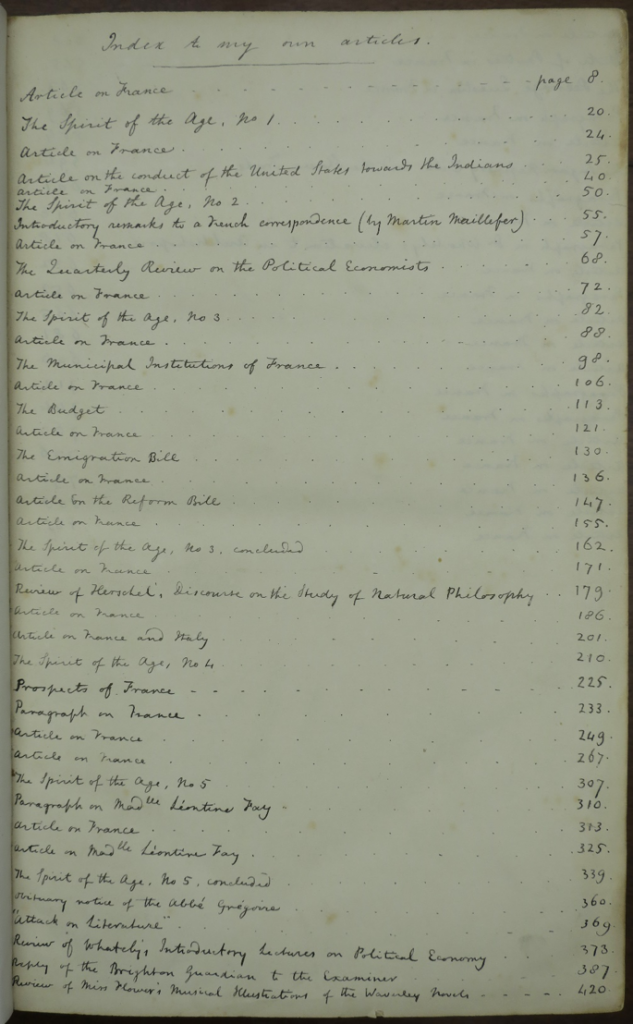

Much to the benefit of those who would become his later scholarly editors, Mill was impressively assiduous when it came to documenting his early newspaper writings. Four of the five volumes of the Examiner held at Somerville contain painstaking lists like this one, handwritten onto the front flyleaf of the 1831 volume by Mill himself:

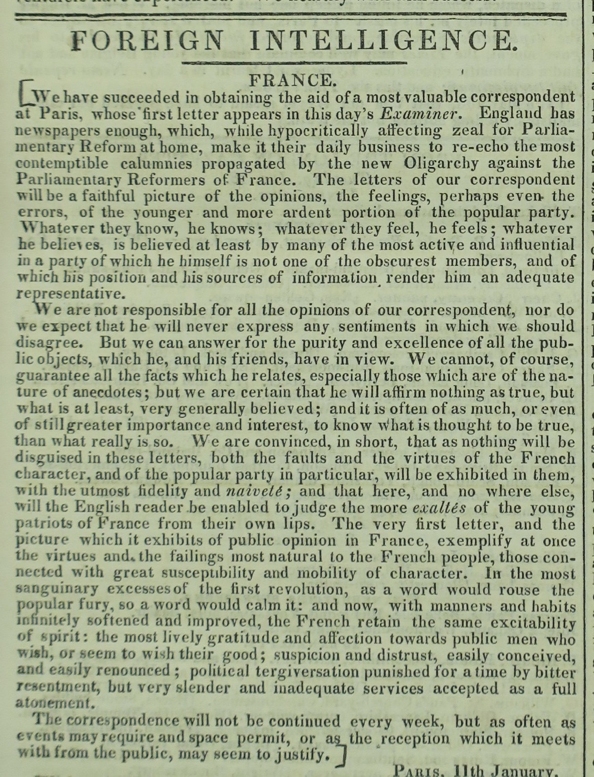

Similarly, in four of the five volumes, Mill has indicated the printed limits of the articles, themselves, by means of square brackets, as with this brief summary of “Foreign Intelligence” from p. 55 of this same volume:

He was quite obviously proud of his numerous contributions, which ranged from his series on “The Spirit of the Age” (which elicited Thomas Carlyle’s appreciation and became the basis for their friendship) to leading articles on French affairs to brief paragraph-length summaries of stories from other newspapers.

Once donated to Somerville, however, not all of these works were read with the same attention or intellectual priorities. Rather than favoring early editions of Mill’s major works, students appear to have read the last published editions, provided, of course, that they were printed in Britain. American editions of Mill’s books are virtually devoid of marginalia, even when printed more recently than their British counterparts. And rather than marking and annotating with an eye toward revision and later republication, students seem to have sought out Mill’s pronouncements on induction or free-market capitalism in order to acquire the basic ideas and/or dispute the major premises.

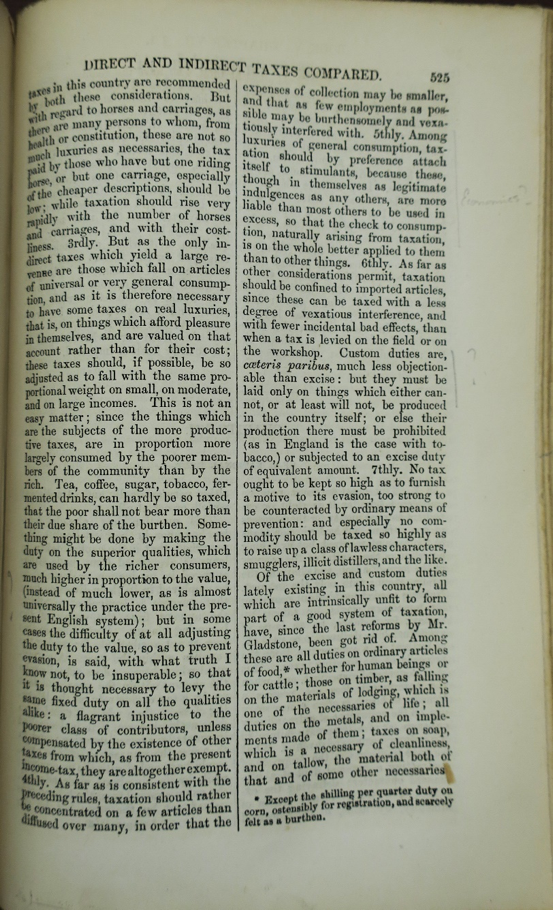

The posthumous one-volume cheap editions of both System and Principles show signs of especially significant student use, despite the fact that their two-column format, smaller typeface, and flimsier paper make them less easy to read than previous versions. For instance, dominated by scores of scores and a small army of marginal question marks, Principles moved one student to wonder about the text’s advice concerning taxation and the field of economics:

Whether this query was made in the era of Edward VII when the book was first donated or of George VI would be interesting to know, as “Economics?” would have meant rather different things before and after two world wars.

Mill’s periodical contributions, including his carefully documented newspaper articles, bear no obvious signs of being read by students at all. Which makes my work easier, of course, but which also makes me wonder whether and how contemporary scholars’ considerable output of articles, essays, occasional writing, and reviews (to say nothing of blog posts) might be read by students of the future.

— Albert D. Pionke, Project Director