Two pieces of good news, just in time for Valentine’s Day.

First, Talking History, hosted by Patrick Geoghegan and produced by Susan Cahill on Newstalk (Irish radio 106-108fm), recently devoted an hour-long show to “John Stuart Mill: A Life.” Among the experts recruited for the really stimulating conversation were Graham Finlay, Mark Philp, Richard Reeves, and yours truly. Many thanks to my fellow panelists and to Patrick for making it more of an intellectual love-in than a massacre, with special appreciation to Richard for his shout out to Mill Marginalia Online. Those interested in listening for themselves should follow this link to the podcast:

https://www.newstalk.com/shows/talking-history-234948

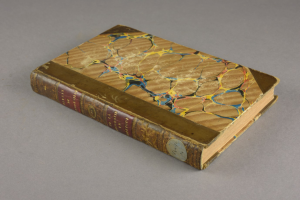

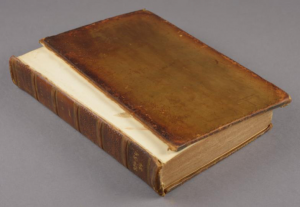

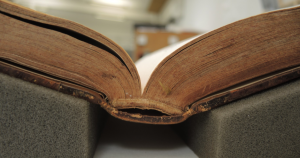

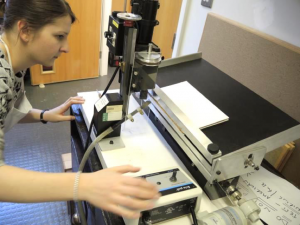

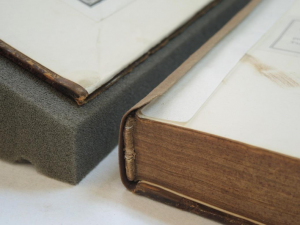

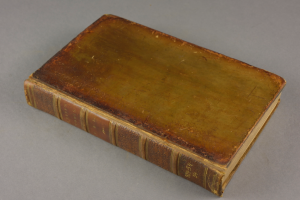

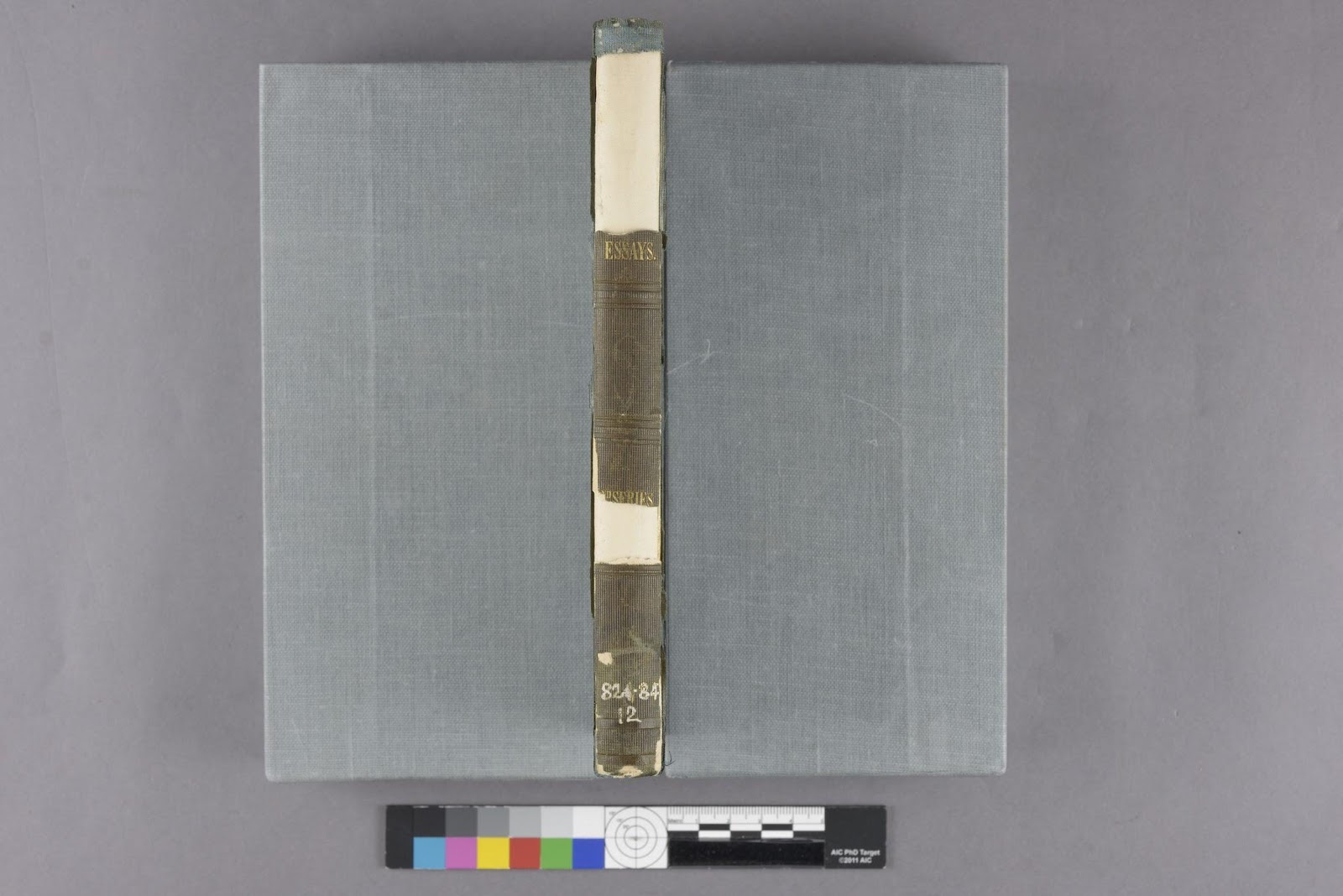

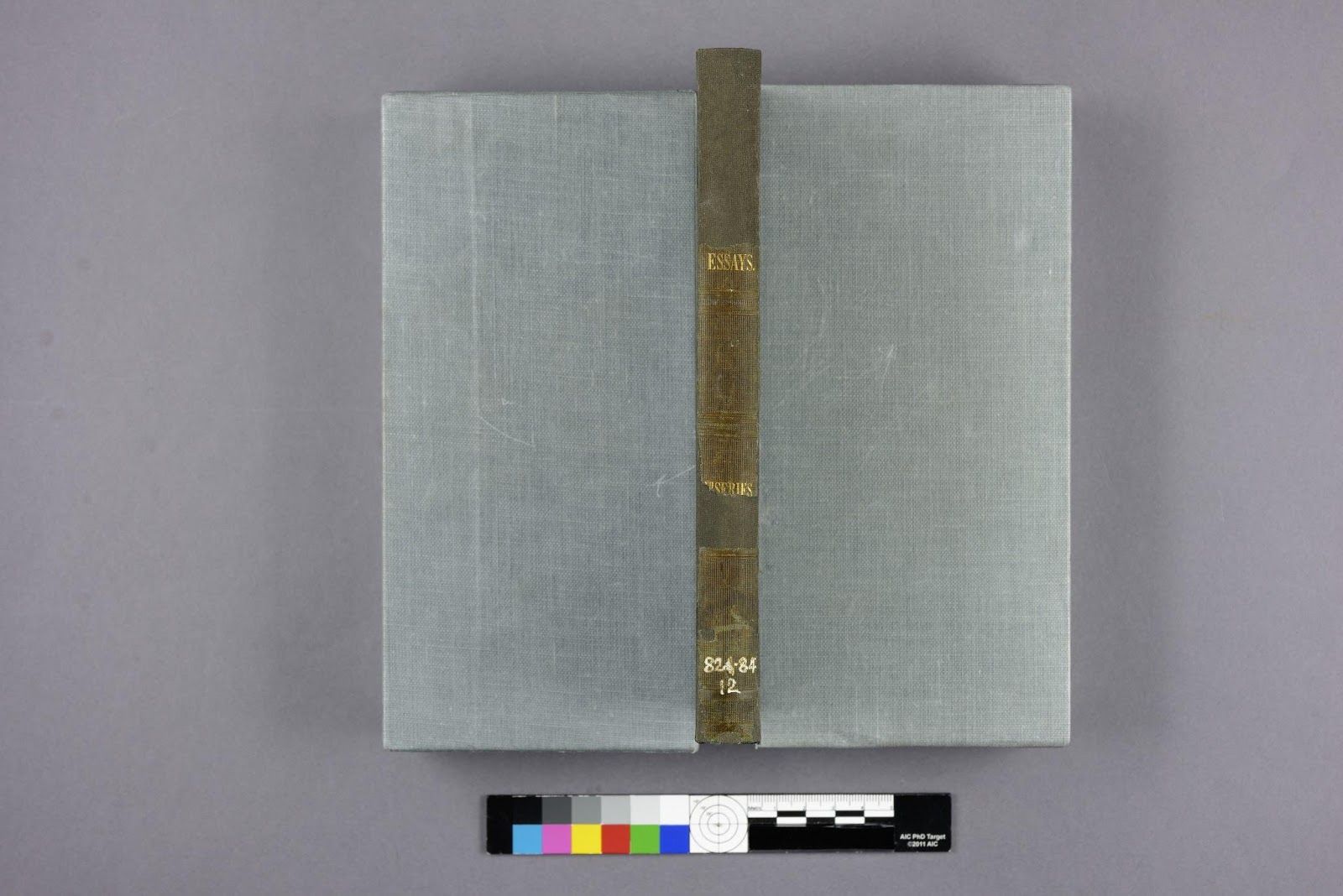

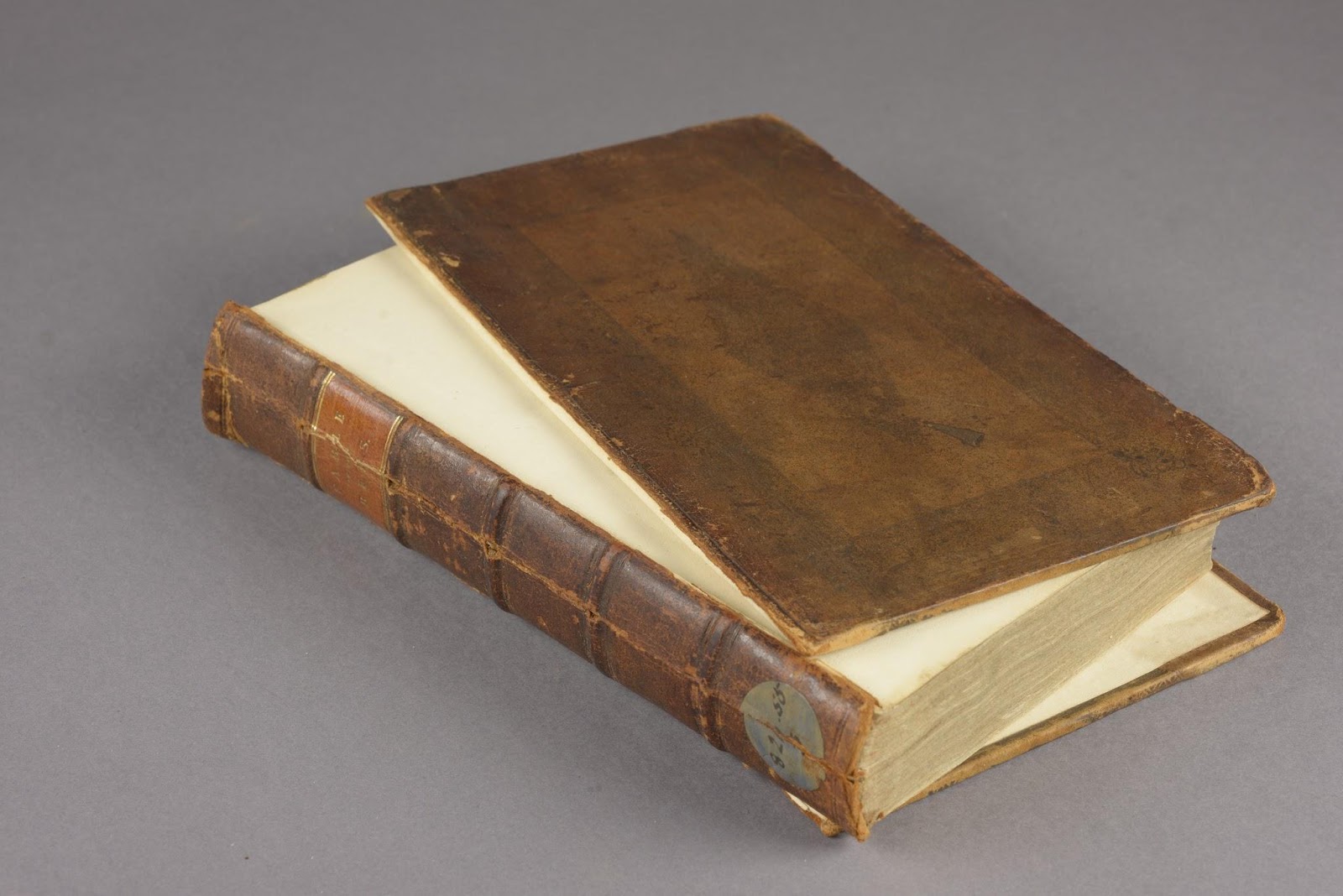

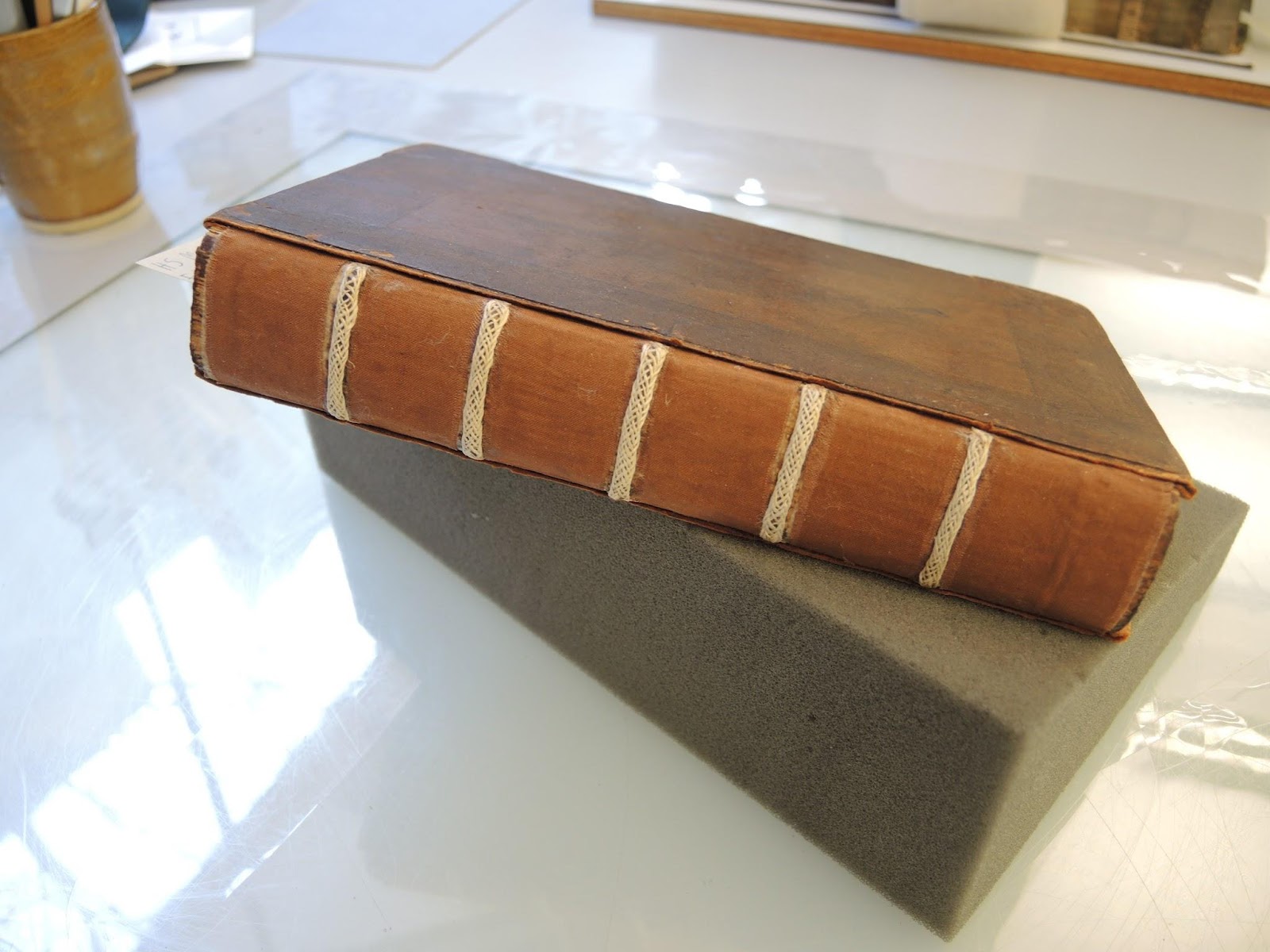

Second, Anne Manuel and I just received word that our joint application to the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation for support for hyperspectral imaging was approved. Having previously identified 163 pages from seven titles across ten individual volumes that have marginalia that is currently unreadable, even with the aid of photographic enhancement, we plan to submit them to David Howell, Head of Heritage Science at the Bodleian Libraries, for spectroscopic analysis. For more on this fascinatingly technical side of library science, follow this link to the Heritage Science home page:

https://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/our-work/heritage-science

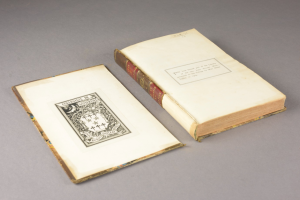

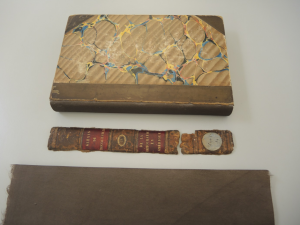

We strongly suspect that significant marginalia by John Stuart Mill resides in John Locke’s Works(1823) and Richard Cobden’s Speeches on Questions of Public Policy(1870), by James Mill in Henry Thornton’s Enquiry into the Nature and Effect of the Paper Credit of Great Britain(1802) and William Spence’s Britain Independent of Commerce(1807), and by David Ricardo in William Blake’s Observations on the Effects Produced by the Expenditure of Government(1823). Time will tell whether we were right. We are grateful to the Delmas Foundation for making this line of inquiry possible.

—Albert D. Pionke, Project Director